Thursday, April 30, 2009

Three Myths About The Translation Business

Metamorfose Vertalingen,

Catharijnesingel 85,

3511 GP UTRECHT,

THE NETHERLANDS

metamorfose.vertalingen@gmail.com

http://www.metamorfosevertalingen.nl/

The native speaker principle is overrated, and the academic concept of ‘quality’ means little in a business context. Statements such as these may sound offensive to translators and clients alike. Yet those who plan to start up a translation business should be aware that the received views of the translation establishment may have little to do with reality.

There are countless languages in the world, most of which have many thousands and some even billions of monolingual or bilingual speakers. The laws of statistics would seem to dictate, therefore, that any attempt to set up a translation business is futile, if only because the number of potential competitors is overwhelming. However, once you have begun your translation business you will realise that serious competition – i.e., from rivals with business acumen and the nerve to question translation myths – is in fact comparatively scarce.

Native speakers are generally held to be indisputable authorities on translation issues. This leads us to the first myth about the translation business: the native speaker is infallible. When you start up your own translation business you will soon discover that most customers, especially the more knowledgeable ones, will demand that the translation be done by a native speaker, on the assumption that a native speaker is automatically a good writer. Not so. While there may be over a billion native speakers of English worldwide, only a fraction of them can be relied upon to possess the judgement it takes to decide whether a translation is linguistically sound in a given business context. We should not automatically assume that a native speaker is a good writer in his own language, and even less that he is a good translator. For one thing, translation requires thorough insight into the source language as well as the target language. When you hire translators for your business, you should never forget that while a good translator is usually a native speaker of the target language, not all native speakers are good translators.

The second myth about the translation business has to do with client priorities, and the assumption that more than anything else, clients want quality. People can be excused for taking this myth seriously. Anyone in his right mind would expect that the client’s main concern when engaging a professional translation agency is to get a high-quality translation. Not so. Studies have shown that most clients are in fact more interested in speed than in quality. This is not to say that your client will be pleased to accept any trash as long as he gets it fast; the point is that quality standards in a business context are different from those in an academic context, and may be overshadowed by practical concerns. University students are trained to achieve linguistic perfection, to produce translations formulated in impeccable grammar and a superbly neutral style. Yet the fruits of such training may not be quite to the business client’s taste. In fact, there are probably as many tastes as there are clients. A lawyer will expect you first and foremost to build unambiguous clauses and use appropriate legalese; a machine builder requires technical insight and authentic technical jargon; and the publisher of a general interest magazine needs articles that are simply a good read. What all clients tend to have in common, however, is a reverence for deadlines. After all, when a foreign client has arrived to sign a contract, there should be something to sign; when a magazine has been advertised to appear, it should be available when the market expects it. In a business environment, many different parties may be involved in the production of a single document, which means that delays will accumulate fast and may have grave financial consequences. So, starters should be aware that ‘quality’ equals adaptability to the client’s register and jargon, and that short deadlines are as likely to attract business as quality assurance procedures.

And if you manage to attract business, you will find that the translation industry can be quite profitable, even for business starters. The third myth we would like to negate is that translation is essentially an ad hoc business with very low margins. Not so. Various successful ventures in recent years, for example in the Netherlands and in Eastern Europe, have belied the traditional image of the translator slaving away from dawn till dusk in an underheated attic and still barely managing to make ends meet. It is true that the translation process is extremely labour intensive, and despite all the computerisation efforts, the signs are that it will essentially remain a manual affair for many years to come. Nevertheless, if you are capable of providing high-quality translations, geared to your client’s requirements and within the set deadlines, you will find that you will be taken seriously as a partner and rewarded by very decent bottom line profits.

About the author

Fester Leenstra is co-owner of Metamorfose Vertalingen, a translation agency in Utrecht (The Netherlands). After having worked for several translation firms in paid employment, he took the plunge in 2004 and incorporated his own company.

For further details about Metamorfose Vertalingen, visit:

http://www.metamorfosevertalingen.nl/

http://www.beedigd-vertaalbureau.nl/

http://www.vertaalbureau-engels.nl/

http://www.vertaalsite.eu/

http://www.oost-europavertalingen.nl/

http://www.scandinavie-vertalingen.nl/

http://www.medisch-vertaalbureau.nl/

http://www.technisch-vertaalbureau.nl/

http://www.juridisch-vertaalbureau.nl/

Corporate Blog of Elite - Professional Translation Services serving ASEAN & East Asia

Wednesday, April 29, 2009

Working your workflow

The Language Technology Centre

It is no secret that optimal processes mean optimal productivity, which in turn means hugely increased competitiveness. Given that we all agree on this, it is surprising to see how many language service providers (LSP’s) out there are not getting the most out of their processes. Let’s look at a few simple things you can do to make sure that your processes are - and crucially - stay the best they can be.

At LTC we have been consulting on the optimization of language related workflows for over fifteen years. We have seen the processes of operations of all sizes – from small start-ups to large language service providers (LSP’s) and corporate language departments – and for many different types of service from translation, localization, and interpreting to subtitling and publishing.

We found that no matter how big or small, how specialized, or multifaceted an operation is, each has its very own approach to managing the complex projects we face in the language industry. Many of these processes grow organically. As a start up company grows and takes on more jobs and employees, others are designed at some point in time to represent perfect use of resources and software tools available to an organization. As these workflows are used, they become second nature to everyone involved. These work flows are ‘the way things are done’ and rarely questioned or reviewed unless there is an acute need to. Why fix what isn’t broken?

It is true. Why think about changing processes that work for you? Many companies only consider their processes or bring in consultants to do so when absolutely necessary. When a large contract is won suddenly, for example, or when processes have become so glaringly inefficient that something simply has to be done.

It is no secret that our industry is changing rapidly. For one it is growing. We all know that the percentage of non- English speaking Internet users is growing, that markets are opening up for a host of industries in non-English speaking countries. We know that the amount of information that needs to be translated and localized and the need for other language services such as interpretation will inevitably grow. Are you ready to claim your piece of this ever growing cake?

The way we work is changing rapidly too. Translation memory technology dramatically changed the way most of us operated in the nineties and development is ongoing. Are you aware what is being developed? Are you ready? But that’s not all. We see ‘per word’ prices plummeting as communication technologies make it possible for companies in low cost countries to set up huge project management operations using the same high quality freelance translators we do. Western LSP’s will only be able to keep up in the price war by significantly improving their efficiency.

So, what next? The good news is that you can be ready for the challenges ahead. Just keeping a close eye on your processes and taking a little time regularly to examine them has many of benefits. You don’t have to change a thing – reminding yourself of what you do, why, and how, will help you not only to see which parts of your process can be optimized and where extra training will improve productivity very quickly, but you will also be able to respond to change, growth, or new challenges more easily. There is a lot of technology out there that can help you, both on the linguistic and business management side. Being aware of your workflow means that you will be able to make very quick decisions on which technology will actually benefit you.

Knowing your processes can have even more advantages. It might help you identify your unique selling proposition – the factors that you can promote as unique for your operation sales and marketing purposes.

Let’s get started then! I suggest you get a pencil and paper ready:

The first step is to draw what we call your ‘company workflow’. It describes the process and players involved in every step that takes you from a quote request to a paid invoice. Just draw a box for each step in your workflow and write the person responsible next to it. The example is just a quotation workflow - you can obviously have more, less or different steps and yours will go all the way to the invoice. In this process ‘project management’ is just one step of many.

The second step is to draw your project workflows in the same way. Some companies that offer only one service in one way may only have one workflow, the more services you offer, the more workflows you will be able to draw. When we talk about offering multiple services, we do not only mean offering translation and interpretation. For example, do you offer an express service? Or do you work with clients that have certain special requirements such as special QA or approval steps? How do you deal with such services? Is your ‘express’ service the same as your normal service with tighter deadlines or do you have a special workflow to maximize efficiency?

After visualising these processes you may already see some room for improvement. Or maybe get that warm glow from the inside as you’ve just proven to yourself that you are currently working in the best way possible. Keep this diagram safe. It will help you whenever you consider introducing new software tools or different processes.

Next you should review which tools you use to optimize these workflows. At LTC we believe that companies should be able to choose a ‘toolbox’ of linguistic and business tools that supports their unique workflow and their customers’ requirements optimally. There are so many developers of tools for the language industry out there – are you sure you’re using the right software for your operation? We suggest that every company should plan regular re-evaluation of tools they use. Many smaller companies, for example, quickly outgrow integrated solutions that cover both the business and linguistic side of their work. Often, innovations come to market that savvy quick adopters can use to gain an important head start. Have you, for example, ever considered the impact of using controlled language tools or machine translation in your authoring, translation or localization process?

We have discussed your processes and have thought about the tools you use in your bid to be as efficient and thus as competitive as possible. All of our effort has centred on being aware of and optimizing your specific company and project workflows for the services you offer. We believe that there is even more to be gained from being aware of your processes and choosing your tools carefully. Let’s end this article with a few ideas that may be food for thought.

I have browsed many websites and found a bit of a theme among small to medium sized LSP’s. Most of you advertise your services with two messages: the length of time your company or the company’s founder has been in the industry and your most important clients. In a market with many competitors offering similar services you rely on the languages you offer, your experience and your previous clients as the only unique selling proposition to your potential clients. What a waste! Recently I worked with an LSP that had a number of sales people who would be in contact with clients and create quotes that were then always checked by the company owner personally. To him this was the natural way things should be, and many of us can see where he was coming from. After all, a well-calculated quote can make or break a sale and is crucial for the profitability of a company. However, he did not see that his approach was one that set him apart from many other companies. Had he been aware of this, he could have created a marketing campaign centred on his offering ‘a most personal service’, for example. So why not take another look at the diagram you just made of your processes? Can you see anything in there that you should shout about? That sets you apart from the rest? You never know, it might just be the point that convinces your potential client to buy your services rather than choosing the competition.

There is another strong argument for spending a little time to optimize your processes and to shop around for the perfect ‘toolbox’ of software for your services. The more unique your company, the more thought has gone into creating processes and methods to offer your services, the more valuable it becomes. Anyone who has some entrepreneurial spirit, is computer savvy, and has some contacts, can buy an integrated system and offer basic language services. If you can generate added value by creating something special, which should not only maximize efficiency and thus competitiveness, business and profit, it could also increase your company’s overall value.

The Language Technology Centre is based in London and Washington DC. It develops business information systems for the language industry and offers consultancy to corporate language departments and LSP’s on process optimization and software implementation.

ClientSide News Magazine - www.clientsidenews.com

Corporate Blog of Elite - Professional Translation Services serving ASEAN & East Asia

Tuesday, April 28, 2009

How To Use Outsourcing To Beat Your Competition

By David Riewe,

The Internet Marketer and Publisher,

Ft. Worth, TX, U.S.A.

david[at]riewe.com

http://riewe.com/

Outsourcing is when you hire outside professionals or services to take on part of your business workload. You may want to outsource part of your work because you don’t have the room, you need an expert, you have periodic busy periods, or you need more production to get orders out on time etc. You could outsource accounting, secretarial tasks , factory help, computer training, web design etc. Below are ways to use outsourcing to beat your competition.

By outsourcing part of your workload you can save time and spend more time concentrating on beating your competition.

- you won’t have to take time training new employees

- you won’t have to do time consuming tasks like adding on new equipment

- you won’t have to learn a new software program or other equipment

- you won’t have to interview employee candidates

- you won’t have to fill out all the complicated employee paper work like tax forms, scheduling, retirement plans etc.

By outsourcing part of your workload you can save money and spend more money on marketing or advertising to beat your competition.

- you won’t have to buy extra office and other equipment

- you won’t have to buy extra office or work space

- you won’t have to spend money on employee costs like taxes, medical, vacation time, holidays, workers comp., unemployment costs etc. (these may vary by which country you do business in)

There are many other ways outsourcing can help you beat your competition. Here are a few more:

- the extra help can help you complete and deliver orders faster

- you could expand your market share by becoming the middleman and offering your subcontractors services or products

- you could end up getting orders from your subcontractors

- it will allow your business to take on extra or large orders

Corporate Blog of Elite - Professional Translation Services serving ASEAN & East Asia

Monday, April 27, 2009

Forward thinking LSP slays inefficiency beast with best-of-breed connection solution

President & CEO - Syntes Language Group, Inc.,

By Robinson Kelly,

CEO and Co-Founder - Clay Tablet

With all the recent buzz about “closing the gap” between the enterprise and the translation frm, the dire need for “automated processes” and the demand from clients for language service providers to keep costs in check while providing better service and faster turn around time, every LSP is wondering: “How do I deliver?”

Forward thinking LSP’s are taking several steps to meet all these goals. This is the story of how one forward thinking LSP took charge of the challenges and proactively slew the beast of connectivity with one very fexible sword.

Syntes Language Group is a Colorado-based LSP that has been around for a long time – 20 years since its beginning in Houston as Global Translation Services. Twenty years seems like ages in our fast moving industry. To give you a sense of history, the first two word processing programs used by Syntes (Farsight and Borland’s Sprint) are long gone, and when then Global Translation Services purchased its first 40 MB hard drive, they were hot stuff! As early adopters of technology, Syntes transferred files using modems and a bulletin board system, way before anyone knew what the Internet was. Their project managers were conversant in Kermit, X-modem, Y-modem and all of those “languages.” Their vendors resided in a DB II database. Forward thinking stuff in those days!

As several LSPs have done over the years, Syntes developed its own proprietary “project management” system and used many different translation tools from the very beginning of the technology. Their frst TM tool was IBM Translation Manager, another dinosaur. For many years, they wrote their own routines, flters and ad-hoc programs to analyze, process and manage client fles. At the same time, they continued to improve on their processes and workfows, and implemented different TM technologies from several software vendors. Meanwhile, the number and complexity of client fles continues to increase.

With all this technology in house – the question became – what’s the next level? How can we be even more effcient? And how can we do this in a manner that directly ben-efts our clients?

First off – Syntes examined their challenges. They came up with the following assortment:

Many clients have legacy systems that require tedious and error -prone manual labor to extract and return text .

This is more common than ever suspected. For instance, they have a client that has to manually extract lots of different items and content from a database then populate a spreadsheet (or several), which they then email over for translation. Syntes then returns a spreadsheet and then the client manually puts the content back into the database.

Fun factor for the client? Zero. Effciency Rating? 0.0001. Reliability index? -10. Bad news all around for any client with legacy systems.

Clients who have developed o rare developing their own custom CMS solutions.

This is also far too common. While clients should usually choose a commercially available CMS product - some firms are just committed to doing it themselves. And while this is sometimes defensible, trying to build a “translation module” into their CMS is not. But they try and this is a path fraught with inefficiencies.

If Syntes were to work within the CMS, then the client can’t use all of Syntes’ TM solutions, without a lot of manual labor on both sides.

If a client really wants their own custom CMS, they should at least be able to send their content in such

a way that it can easily use all available technologies and processes on the translation side so they can deliver faster time-to-market, additional consistency and quality, and cost efficiencies.

Some clients require Syntes to access varied CMS systems to extract content and put it back in.

This is the classic “if you want our work you’ll come get it” approach. We know an LSP who interfaces with twenty-two different systems on a daily basis! Not a good way to be efficient. In addition to the manual effort required in getting the content, there’s no way to leverage TM or Terminology management, etc., Further, there’s a huge learning curve for each and every systems and each and every resource who has to interact with each system. Lastly - there’s no back up strategy when a resource is absent, or leaves - unless you’re going to train every resource on at least TWO systems. There’s a word for this - inefficient.

Clients with disparate or varied departments or Business Units, use different ways to manage their content and documents.

This is very common in larger firms that have grown through acquisition, making new business units out of the recent takeovers and leaving existing content and document management systems in place.

In these scenarios - there’s no way of providing any centralized control, reporting or status. There’s no way to know what’s going on across all these systems and this provides a challenge for both the LSP and client as they struggle to get visibility across all the systems and projects.

This is quite a list and proved a bit of a challenge.

Enter Clay Tablet .

Syntes’ Beatriz Bonnet had met the CEO of Clay Tablet, Robinson Kelly at Localization World in Montreal in 2006 and the two hit it off instantly. Recalls Kelly, “She knew every translation technology standard out there, and I thought to myself – here’s an LSP owner who fully gets technology.”

Bonnet was intrigued – here was a company marketing a connection technology that might meet all these requirements – could it ft the bill? She started her analysis, but not without first putting Kelly and his staff through

the paces and looking at many demos. Over the last year, Kelly and Bonnet continued to get to know each other’s company and discussed how collaboration between the two companies might work. And Bonnet continued to analyze all the options to best serve Syntes’ clients. She continued to talk to the clients exhibiting the problems outlined above and their plans for the future. To some extent, she hoped that more of them would move to a more centralized, single commercially-available CMS. It soon became obvious that companies sometimes have good reasons to stay with their legacy system, or to move from a legacy system to a newer custom CMS system.

Remembering all the interactions with clients and with the Clay Tablet folks, it started to become obvious that the best way to serve Syntes’ clients was to officially partner with Clay Tablet and work as a team to gain additional efficiencies and offer clients a solution that can make project managers’ jobs everywhere significantly easier. Our partnership became official in December, and we have already identified key opportunities to add value to Syntes clients. Because Clay Tablet is connectivity software and not a translation management solution, each company is allowed to focus on what we do best. Syntes clients can run their core businesses without having to become experts in translation and localization – a course many companies are not willing to take. Clay Tablet can focus on connecting disparate CMS systems to different TMS systems without becoming another TMS tool. And Syntes Language Group can focus on what it does best: serving the translation and localization needs of its clients with excellence without having to become a software shop.

Talk about a win-win-win!

ClientSide News Magazine - http://www.clientsidenews.com/

Corporate Blog of Elite - Professional Translation Services serving ASEAN & East Asia

Sunday, April 26, 2009

Tips for OpenOffice.org Writer

a technical translator & a freelance contributor

From: www.translatewrite.com

INSRT STD HYP?

Most users don't give much thought to the cryptic INSRT STD HYP fields in the Status bar. However, sometimes they can come in quite handy. When you click on the INSRT field, it changes its status to OVER. Now, if you start typing in a currently opened document, you will notice that the typed text overwrites the existing text. Use this feature when you want to replace a text segment and don't want to waste time on selecting and deleting it first. The STD field controls the way the selection works, and it has two additional modes: EXT and ADD. This feature can be useful if you use your keyboard to select text segments. Try this: select some text, click on the STD field, and it switches to EXT. Now you can use the arrow keys on your keyboard to extend the current selection. Click on EXT, and it changes to ADD; use the arrow key to move the cursor to another text fragment, press and hold the Shift key down and use the arrow keys to add a new selection. The default mode of the last field is HYP, and it allows you to launch hyperlinks in the document. If you want to edit the link, click on the HYP button, and it changes its mode to SEL. Now you can click and edit the hyperlink without launching it.

Using AutoCorrect to insert frequently used special characters

Using Insert Special character, you can easily insert symbols and other signs. That's fine if you need to insert a symbol every now and then, but what if you have to insert a particular character in almost every sentence? One way to solve this problem is to use the AutoCorrect feature. Let's say you need to insert the character µ; choose Tools > AutoCorrect, click on the Replace tab, and create a new rule that converts the specified string to µ, for example, #m. Once the rule is added, you can simply type #m, and Writer converts it into µ.

ODFReader

Instead of using a stand-alone viewer, you can view Writer documents directly in the Firefox browser. To do this, you have to install a tiny extension called ODFReader. Install it by clicking on the Install link, restart your browser, and you are done.

Inserting data from a data source to Writer document

Let's say you have a list of quotations in a spreadsheet file, and you want to access it from within Writer so you can easily insert a quotation into your Document. First of all, create a new Base database that uses the spreadsheet as its data source: Choose File>New>Database, select the Connect to an existing database option, select Spreadsheet from the drop-down list. Make sure the Yes, register the database for me option is selected and press Finish.

1. Open the Writer document and place the cursor where you want to insert a quotation.

2. Press F4 to open the Data Source window.

3. Choose the table (sheet) that contains quotations.

4. Select the quotation record (row) you want to insert and press the Data to Text button.

5. Select the fields you want to insert and press OK.

Dmitri Popov works as a technical translator from English and Danish to Russian, as well as a freelance contributor to major European and US computer magazines and websites. His articles cover open source software including desktop and web-based applications and tools. Recently, Dmitri released the book Hands on Open Source, which provides a practical introduction to the best open source applications.

Corporate Blog of Elite - Professional Translation Services serving ASEAN & East Asia

Saturday, April 25, 2009

How About Taking a Shortcut?

Brazil

ego@uol.com.br

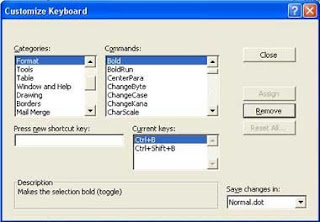

For people like us, who spend so much time in front of the computer making the same movements (which often lead to repetitive stress injuries), any timesaver can be useful. Keyboard shortcuts can help immensely, and even allow you to do things that are impossible with the mouse.

For instance, to access any menu, you can use the Alt key plus the underlined letter in the menu bar. When the menu opens, you can choose a new letter to perform the task you want. In Word, for example, simply by pressing Alt+A+I, you can insert a table into the document, or count the words in it with Alt+T+W. Looking at the menus, you can see that most of the actions have a shortcut next to the command. Memorizing the ones that you use most can save both time and arm movements. Furthermore, many times you can get the same result with more than one shortcut, so you can select the one you like best.

Start

Most keyboards have a key marked Windows or Start that few people use - it can be found between the Alt and Ctrl keys, to the left of the space bar, often times displaying the Windows logo. However, combined with others, this key performs a variety of important functions:

Start+D: By pressing Start+D at the same time, you can minimize all open windows. By pressing these two keys again, you can maximize them once again. If you first press Start, you will see that the Start menu opens. If you then press D, a list of the last opened documents will appear. Then simply move the down arrow until you reach the desired document and press Enter to open it. By doing this you do not have to open the corresponding program first or search through various levels of folders. This proves very useful when you are working with more than one type of program, such as a Word file with a PDF document as reference. It is also extremely helpful when you open a document and soon after can no longer find it because you do not know where it was saved (however, this will only work if you do not open too many files afterward).

Start+P: Displays a list of the programs installed on your PC. If the most frequently used ones (such as your favorite dictionaries) are right at the top of the list, simply press the down arrow until you reach the one you are searching for and press Enter to open it.

Start+Tab or Alt+Tab: Alternates between open files/programs.

Undo/Redo

Another extremely useful command is Ctrl+Z (or Alt+Backspace), which allows you to undo any mistake. If the file has not been closed or saved, you can go back indefinitely undoing each wrong action. If you go past the point you wanted, press Ctrl+Y (Ctrl+R or Alt+Enter, depending on your program) to redo the action.

Now let us suppose I am translating (or even worse, revising) a file and the program freezes. Forced to close the program unexpectedly, how can I find where I left off? If you open Word again and press Shift+F5, the file will return to its last saved change and I can continue revising or translating from this point onwards. This command can also be used when you want to check or copy a portion of text somewhere else in the file and then return to the point where you left off. For instance, if you want to check the first topic of this file and then return here, simply press Ctrl+Home and then Shift+F5).

Formatting Shortcuts

I believe that most people know the commands for simple formatting. I personally use Ctrl+U for underline, Ctrl+B for bold; Ctrl+I for italics, Ctrl+Shift++ for superscript and Ctrl+= for subscript. However, I also have two other little tricks that I frequently use. The first is Shift+F3, which alternates between lower case, First Letter Upper Case and ALL UPPER CASE. This is excellent for those times when you have the Caps Lock key pressed and only realize it afterwards. It also helps when you want to copy a portion of text with different formatting, such as a title in capital letters to the body of the text.

Another trick is to copy the formatting of a word or paragraph, no matter how complicated it is. If you want to format a word, simply place the cursor over the word and press Ctrl+Shift+C. Then go to the word (or portion) on which you want to paste the format and press Ctrl+Shift+V. This is useful when you copy something from a glossary or from the Internet and paste it into a work file whose formatting is different. All you have to do is copy the formatting of any neighboring word and apply it to the text.

Now, if you want to copy the formatting of a paragraph, highlight the whole paragraph and perform the same procedure above: press Ctrl+Shift+C, go to the paragraph(s) you want to format and press Ctrl+Shift+V.

The best thing about this command is that it remains available until you apply a new format or until the file is closed, and it can be used as many times as you want. It is also unbeatable when dealing with numbered lists with text inserted in the middle. Copy the first paragraph of the list and then apply it when needed. The numbering will continue from the point where you stopped.

These are some of the shortcuts that have most helped me, but you may very well have other preferences. Besides, the version of your program might be different than mine (Windows 98 SE), and therefore the shortcuts may differ as well. For a complete list of Word shortcuts, press Alt+F8 and once the Macro window opens, scroll down the Macros in: list and select Word Commands. Scroll down to choose ListCommands in the window above and click the Run button. In the List commands window, choose Current menu and keyboard settings to open a file with all hotkeys. This file can be saved and modified as you please. Explore your program and try to memorize the shortcuts that best suit your needs. Soon you will see that many things can be done faster and with less effort.

Table with the main Windows XP shortcuts.

Édi G. Oliveira has been a translator for over 20 years, most of which have been dedicated to the biomedical field. With a degree from the University of São Paulo and a post-graduate degree from Paris Vincennes University, she has translated dozens of books for major Brazilian publishers and countless medical equipment manuals, among other projects. Yet she would rather have discovered these shortcuts BEFORE developing tendonitis in her right arm.

This article was originally published in Сcaps Newsletter (http://www.ccaps.net)

Corporate Blog of Elite - Professional Translation Services serving ASEAN & East Asia

Friday, April 24, 2009

Wordfast and Trados

Ampur Muang Chiang Mai, THAILAND,

English to French translation

Translator and owner of www.your-translations.com

Contact the author

This articles gives an overview of features provided by Wordfast and dicusses Wordfast's compatibility with TRADOS

Wordfast and Trados

Well, what is Trados? I already see those smiles on the old timers' faces. Yes, Trados is indeed the leading CAT tool on the market, and is certainly pretty good on that count. If you are a translator, even beginner, you will have noticed a lot of translation agencies around the world request Trados.

The first stable datum you should have on that subject is that you can work on most "Trados-Only projects" using Wordfast.

Unfortunately this fact remains little known to agencies.

If you hang around Wordfast's newsgroup (groups.yahoo.com/wordfast), you will be surprised to notice a considerable number of "wordfasters" actually own Trados... and work with Wordfast.

Before going any further, let clear a point: I have only a limited experience of Trados itself, and I'm not the perfect person to write that article. However, having worked on a number of Trados projects using Wordfast, I thought you might be interested to know how it is done, what are the limits, and what advantages you will gain using Wordfast. If you are yourself a Trados-learned wordfaster, you are very welcome to send me comments, notes, ... about this compatibility issue.

Trados

Okie, so it's time to describe a little bit Trados. Actually, although convenient, mentioning "Trados" is not quite accurate. "Trados" is composed of several different modules, many of which can - have to - be bought separately:

Trados WorkSpace

Trados WorkSpace is an integrated environment allowing you to start the different components of Trados suite and organizing projects, and files within projects.

Trados WorkBench -TWB

What most people call "Trados" is in fact TWB. It handles the translation memory, allows you to analyse your documents, segment them, and clean them. It works in conjunction with other Trados modules and most usually with Word. You have to install a Word template, TRADOS5.dot to work with Word Trados TagEditor. TagEditor is a special text editor used to work with tagged documents, such as html, xml,...It works along with TWB.

Trados MultiTerm

MultiTerm is Trados' terminology solution. It's kind of a dictionary where you can input a term and its translation in several languages, along with definitions,... It is again a separate module but can be called from within Word using another Word template.

WinAlign

Alignment solution. Allows generating translation memories.

Filters

Filters are used to process various formats such as FrameMaker, QuarkXpress,... so that they can be translated in Word using TWB, and restored back to the original format. This is THE strong point of Trados.

T-Windows

T-Windows are separate modules used to handle different formats, such as T-Windows for PowerPoint, T-Windows for Excel, T-Windows for Resources, T-Windows for Clipboard.

Assuming you work with an agency, the workflow with Trados will look like that:

An agency creates a project in WorkSpace, possibly segments/pretranslate the files to be translated, adds relevant glossaries, and translation memory. If the project is originally in a DTP format, such as QuarkXpress files, the agency will usually prepare the files using the filters.

You receive the project - or just the files - import it in WorkSpace, open your files in Word, activate Trados Template, open TWB, open the memory if you have one, create one if you don't, open MultiTerm if applicable - meaning, if you have a MultiTerm glossary - start a session and translate the damn thing. When the translation is over, you save the segmented files and turn them back in. (unless asked differently)

Your agency imports the files, and if you are lucky enough, you will cash your check on time. :-)

This simple routine will get you through in most cases. Okie. So that enough of an overview. Actually, I should charge Trados for it since you can't find anything that clear on their site. ] ;-p

With Wordfast

Now, as a translator, how would you work on that Trados project using Wordfast?

Simple. Start at step #2: You get the files, along with the memory and the glossary. (a Trados project is fundamentally a tree structure where you simply pick up the files to be translated,...). You open the files in Word, open the memory in Wordfast, open the MultiTerm files as glossaries and start translating as usual.

If your files were segmented by the agency, Wordfast will use those segments. If the document is not segmented, Wordfast will segment it in pretty much the same way as Trados does and unless you exactly know what to look for, it will be close to impossible to differentiate a document segmented with Trados from one segmented with Wordfast. Translate your files as usual using Wordfast, turn the segmented document in and go to step # 3, cashing your check.

There are small segmentation differences however. The main thing you need to remember is that Trados does NOT support empty segments while Wordfast may. So if at anytime you wish to leave an empty segment, type in 2 spaces. Trados should have no problem whatsoever to clean your files, update it's TM, integrate them in the project,... In fact, your client might never know you did not use Trados. I recommend you tell him anyway, for the sake of honesty, if nothing else.

Note: You can not read directly Trados 5.5 memories, as they are encrypted. (While Trados officially advertise "improved compatibility"). This however is not a big deal. Simply ask your client to provide you with a tmx memory. That should take him a couple minutes to do so. Note also that Wordfast can not produce a native Trados memory (tmw), but can produce a tmx that will import perfectly in Trados

That covers the largest volume of translations. Trados prepared files such as QuarkXpress tagged files, MIF tagged files,... are in "rtf" format and as such will be processed by Wordfast quite nicely using the above procedure.

Compatibility Limits

Where are the limits? What can and what can't be done in respect to this compatibility issue? Are there workarounds or is the issue a big No-No? This is not a comprehensive list as yet, and you are very welcome to send me comments and notes about it. I expect this page to be growing over time. Anyway. Here we go:

TM issues

As mentioned in the previous page, you can not open TWB 5.5 memories in Wordfast. The only workaround for that is to get someone to convert the memory in either "tmx" or "txt" format. That someone will usually be your client, but any Trados 5.5 user would do,...and there are plenty of them on forums that won't mind helping you out, possibly for a symbolic fee. The second TM restriction is that you can not produce "tmw" memory*. This is not a problem, because your client doesn't need it really - if you provide segmented files, Trados will update/create the tmw memory, and that's the end of it. You can also send a tmx memory, and Trados will import it without as much as a complaint.

*UPDATE: Wordfast now export *.tmw TMs, Trados native format.

TagEditor

TagEditor is a separate editor and you can not use Wordfast to work with it directly. Besides, I guess you do not have TagEditor, so that's that.

However, in my experience, the vast majority of Trados projects do not require it, and on a technical viewpoint, if you can tag your files (or get them tagged), you can still translate in Word and provide your client with a translated file and a TM. That TM will be usable as usual and heck, the translation is what the client needs.

Filters

Filters are the strong point of Trados. It can handle a hell of a lot of formats, from the well-known DTP to more obscure formats. Wordfast - +Tools actually - is catching up on that bit by bit and is now providing some beta support for "*.mif" (FrameMaker), PDF, HTML, XML, ...

Refer yourselves to +Tools manual for a current list. +Tools is evolving pretty fast, and by the time you read those lines, I might have to remove the word "beta". However, for now, just ask your client to process the files for you (they anyway do it most of the time) and translate paying respect to the tags. (At least bow a couple times and make sure you don't have your shoes on when translating a tagged file.)

Word count

Word count differs between Word, Wordfast and Trados. In my experience, Wordfast wordcount is usually about 5% up compared Trados's wordcount, which is itself about 10% up from MS Word (it varies, of course). This reflects itself in the number of words contained in the fuzzy matches, full matches and so on.

Most usually, your client will provide you a word count with his PO. I suggest you stick to it unless there are very notable differences between both word counts, in which case you should investigate the matter.

(i.e.: I once had a document meant to be mostly 100% matches, and Wordfast could not find them. After sorting the matter out, it came up the client did not provide the right memory!)

Differences come from the fact that the algorithm to count words is different. For instance, this:

tug-of-war.Newspaper

is 1 word in Ms Word, because Word is not programmed to separate the words. However, for the translator viewpoint, we have 4 words...and a typo. Wordfast will rightly count it as 4 words. It takes the same amount of effort then it takes to translate:

tug of war. Newspaper

Further issues

I will expand those issues further when I get the chance to experiment with T-Windows (I don't know much about that) and see what kind of compatibility there is. Wordfast handles PowerPoint, Excel and Access right from Word. :), and you can provide your client with translated files and a TM, but I'm not sure on the way T-Windows handle the matter, so there might be restrictions there.

UPDATE: T-Windows for PowerPoint simply translate and create a memory, so you can work with Wordfast. No problem.

All right, there you have it. I may add more to that tutorial based on your feedback and questions, or Wordfast evolution, but this should be able to get you on the track and rolling. Good luck.

© Sylvain Galibert.

This article is a courtesy of www.your-translations.com, professional English to French translation services. Your-translations.com offers professional translation services and translation project management. More articles from the same author can be found there.

Corporate Blog of Elite - Professional Translation Services serving ASEAN & East Asia

Thursday, April 23, 2009

The Impact of Translation Memory Tools on the Translation Profession

Graduate Teaching Assistant and freelance translator,

The University of Manchester, UK

asaleh1111[at]yahoo.com

Abstract

For different reasons, Translation Memory (TM) tools have become both indispensable and popular. They have caused a sweeping change in the translation market. Translators are no longer restricted to hardcopy dictionaries and glossaries; they can now use online and electronic resources. In addition to all the benefits TM have brought about for translators, translation agencies and clients, they also have some inherent shortcomings. In this article I will explore both advantages and disadvantages of TM for these parties. I will also explain the change TM brought about in the translator's working methods.

In order to conserve time, money and quality, Computer Assisted Translation (CAT) tools, including Translation Memory (TM), have become very popular with translators, translation agencies, and clients. While TM has its advantages and disadvantages for the translator and the translation bureau, it has advantages and virtually no disadvantages for clients.

First, as far as the translator is concerned, the great advantage of TM is in the area of translation quality. The quality is likely to improve in terms of consistency, both in the same document and across documents. TM saves pairs of terms or strings of texts, and reproduces them when the same SL term or string comes along in any other position in the document being translated. This, therefore, helps the translator to maintain consistency by always using the same equivalent for the same term or string. In other words, the translation becomes more efficient and consistent. In addition, a translator can always use the same TM with future translations, albeit from the same client, and hence achieve consistency in terms of terminology and style across translation jobs.

Second, "Terminology mining is said to account for 75 percent of a translator's time" (Arntz & Picht, 1989:234 in Austermuhl, 2001). TM saves the translator's time by sparing him/her the need to look up the terms and words again if they are repeated in the text, especially in the case of large documents, or in another translation from the same client or in the same field of specialization. The translator will translate repeated terms and strings only once and TM will 'translate' them whenever they come up again in the SL which, therefore, saves time. TM also spares the translator from the need to strain his/her memory to remember how s/he translated a certain term or string before or the need to go back through the document, albeit in long documents, to locate it. On the other hand, if TM is provided with the translation job, s/he will simply choose the equivalent used in the TM without need to 'researching' which equivalent to use especially where synonymous or semi-synonymous equivalents exist, which is quite often the case. For example, the translator may not know whether to use 'Sexually Transmitted Disease' or 'Sexually Transmitted Infection', and this is where the role of TM comes in to decide which equivalent has been used before and to maintain consistency. Consistency means better quality which, in turn, means the client will be happy with the translation and will thus be more likely to consider the translator for future jobs.

Third, by saving the translator's time, TM increases his/her productivity which can lead to an increase in income. Further, more and more clients now are not only aware of but also require that their work be translated by TM software. In other words, the use of TM makes a translator more competitive by being distinguished from the others who do not use TM, and more likely to receive work. Finally, TM is quite portable. A translator can, literally, move easily around with all his/her translation resources on a CD or a 'Memory Stick'.

However, TM has its own disadvantages for a translator. First of all, s/he will have to invest a considerable amount of money to obtain the software and to put some time and effort into learning how to use it. Furthermore, especially at the early stages of use, the translator will always need to refer to the manual or ask experienced colleagues about the technical difficulties s/he may encounter, which means loss of valuable time.

In most programs using TM, a translator will only see a few sentences, strings or one paragraph on the screen at a time during the translation process. Therefore, s/he will only be able to work on that sentence, string or, at best, paragraph level and therefore may be translating out of context. As a result s/he may need to change some of his/her translations afterwards, which again means wasting some more time depending on how many corrections s/he needs to introduce in the translation. There may also be a risk of too much consistency in the translation. TM can adversely affect the translator's search for other, and perhaps better, equivalents and restrict him/her to use the same equivalent throughout the document even if there is a better alternative. In addition, if the translator delivers the TM together with the job, this can make the client less dependent on the same translator for future work, since the client can always give a new translator the TM they have received from previous translations together with the job. In other words, while promising a translator an opportunity of more work, TM still carries with it some inherent risks.

For the translation bureau, which manages the translation project for the client, TM also has some pros and cons. On the positive side, as has already been pointed out, more clients now request that their work be translated using TM. This means that having TM will help the bureau secure jobs that could have been lost otherwise. More work means more income. Furthermore, in cases of large translations which are normally divided among several translators, agencies can better proofread and project-manage the work with the use of TM. In the case of a ST being translated to more than one language, a bureau can manage the different target texts (TT's) quite easily and update its own TM accordingly. Other advantages of TM include the fact that agencies will be able to offer competitive prices for translation and can recruit several translators for the same job without fearing loss of consistency when all use the same TM. The only disadvantage of TM for agencies, in my opinion, is that a bureau will have to invest in the purchase of the software and its yearly updates and this outlay is usually high.

From a client's point of view, TM gives them the freedom to use different translators and translation agencies for future translation tasks. Consistency with previous translations is still maintained since clients can always request TM to be handed over with the translation and can later provide it to new translators to use and update. More important is that the client may be able to negotiate a lower fee when they provide TM along with the text to be translated. They may only pay full price for no matches but less (60 to 70%, for example) for fuzzy matches and even less for complete matches (30%, for example). The turnaround time, a major concern for clients, will be quicker because translators work faster and agencies manage the project more effectively. In short, the client has everything to gain and nothing to lose.

From the above one can say that TM may only be used with technical documents where there is a certain amount of repetition. For example, manuals, brochures and balance sheets contain a considerable number of repetitions and also need to be updated quite often. This is where TM comes in to achieve consistency and efficiency. On the other hand, TMs are not likely to be used with literary texts where the context plays a more important role compared to non-literary texts. Literary texts are also characterized by their figurative language which makes them difficult to translate with TM. Finally, literary texts do not seem to have the same amount of repetition as technical texts.

The Impact of TM on the Translator's Working Methods

Pros and cons aside, let us now look at the impact of TM on the translator's working methods. Austermuhl (2001) thinks that "more than any other professionals, translators are feeling the long-term changes brought about by the information age. The snowballing acceleration of available information, [and] the increase in intercultural encounters ... have resulted in drastic and lasting changes in the way translators work." Therefore, the question now for translators is not whether to use electronic tools or not but rather which tools to buy, learn, and use. Electronic dictionaries, glossaries and other resources have an edge over hard copies because they are easy to update and research. In fact some encyclopaedias and scientific journals are no longer published in print but are only delivered digitally (ibid: 102).

With the domination of English over other languages in the world of business, science, and technology, it is not surprising that more translators are now needed than ever before. The volume of translations being carried out each year from English into other languages is huge and worth billions of dollars. In addition, the expansion of the Internet and the computerization of the global economy have changed the way business is being conducted and emphasize the need for more effective and, undoubtedly, faster methods of translation, making full use of the huge amount of data available online. The influence of specialization and diversification, often referred to as the 'information explosion,' is also obvious as the amount of information available is now far greater than ever before and beyond the capacity of the available human brainpower to handle.

With TM the translator switches from the traditional method of looking up words and terms in hard-copy dictionaries, manuals and other written materials and perhaps maintaining hard-copy glossaries, to the world of online resources. A translator can tour national libraries, virtual bookstores, multilingual databases, newspaper and magazine archives, and other sites online, available at his/her fingertips, build up his/her own glossaries and attach them to the TM to enhance its performance. In addition, by developing his/her IT skills, a translator switches from translating only hard-copy documents to the fields of software localization, web page translation, and handling different electronic formats. S/he becomes more competitive because of the range of services s/he offers. As a knowledge-based activity, translation requires new strategies and a "paradigm shift in methodology. This shift must embrace practice, teaching and research" Austermuhl (2001). A translator is no longer someone sitting at a desk with a pen in hand, sheets of paper before him/her and a number of dictionaries within reach. S/he has become a person using a computer, or perhaps carrying a laptop, on which s/he has installed, among other things, several online dictionaries and glossaries. The translator is also someone who uses TM software and has very good IT skills. Translators now receive work electronically in different formats. This is in short the effect of TM on the work of the translator.

In conclusion, TMs have become popular with translators, agencies and clients because they save time and promote better quality and efficiency. Unlike translators and agencies who derive some gains but also some losses from the use of TM, clients only have gains: shorter turnaround, lower cost, and less dependency on the translator/translation bureau. Of all the advantages they have brought about to the translator, TMs have had a great impact on the way translators work now. Translators are now able to make better use of the available resources: electronic dictionaries and glossaries, and spelling checkers. TMs have equipped translators to handle the information explosion in all areas of human endeavor more efficiently than the human brain alone ever could.

References:

- Asensio, R., Translating Official Documents, Manchester and MA, St. Jerome Publishing, 2003.

- Austermuhl F., Electronic Tools For Translators, Manchester and MA, St. Jerome Publishing, 2001.

- Baker, M., In Other Words: A Coursebook on Translation, London and New York, Routledge, 1992.

- Delsile, J., et al (eds.), Translation Terminology, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, John Benjamines Publishing Co., 1999.

- Dickens, J., Hervey, S., and Higgins, I., Thinking Arabic Translation, A Course in Translation Method: Arabic to English, London and New York, Rutledge, 2002.

- Gile, Daniel., Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training, Amsterdam / Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1995, p xiv.

- Hatim, B., Teaching and Researching Translation, Applied Linguistics in action Series (ed. Candlin and Hall), UK, Pearson education, 2001.

- Newmark, P., About Translation, UK, Multilingual Matters, 1991.

- Wagner, E., Bech, S. and, Martines, J., Translating For The European Union Institutions, Manchester and MA, St. Jerome Publishing, 2001.

- Whitelock, P. & Kilby, K., Linguistic and Computational Techniques in Machine T

ranslation System Design, (2nd Ed.) London, UCL Press, 1995).

ranslation System Design, (2nd Ed.) London, UCL Press, 1995).

This article was originally published at Translation Journal (http://accurapid.com/journal).

Corporate Blog of Elite - Professional Translation Services serving ASEAN & East Asia

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

Universal translator

By Wikipedia,the free encyclopedia,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_translator

The universal translator is a fictional device common to many science fiction works, especially on television. Its purpose is to offer an instant translation of any language. Like hyperdrive, a universal translator is a somewhat improbable technology that is an accepted convention in science fiction stories and serves as a useful plot device. As a convention, it is used to remove the problem of translating between alien languages, unless that problem is essential to the plot. To translate a new language in every episode when a new species or culture is encountered would consume time (especially when most of these shows have a half-hour or one-hour format) normally allotted for plot development and would potentially, across many episodes, become repetitive to the point of annoyance. Occasionally, alien races are able to extrapolate the rules of English from very little speech and then immediately be fluent in it, making the translator unnecessary.

While a universal translator seems unlikely, due to the apparent need for telepathy, scientists continue to work towards similar real-world technologies involving small numbers of known languages.[1] See machine translation and speech recognition for discussions of real-world natural language processing technologies.

General

As a rule, a universal translator is instantaneous, but if that language has never been recorded, there is sometimes a time delay until the translator can properly work out a translation, as in the case of Star Trek. Some writers seek greater plausibility by instead having computer translation that requires collecting a database of the new language, often by listening to radio transmissions.

The existence of a universal translator is sometimes problematic in film and television productions from a logical perspective (for example, aliens who still speak English when no universal translator is in evidence and all characters appear to hear the appropriately translated speech instead of the original speech, the ability to speak in the language when direct translation is possible), and requires some suspension of disbelief when characters' mouths move in sync with the translated words and not the original language; nonetheless, it removes the need for cumbersome and potentially extensive subtitles, and it eliminates the rather unlikely supposition that every other race in the galaxy has gone to the trouble of learning English.

Depictions

Doctor Who

Using a telepathic field, the TARDIS automatically translates most comprehensible languages (written and spoken) into a language understood by its pilot and each of the crew members The field also translates what they say into a language appropriate for that time and location (i.e. speaking the appropriate dialect of Latin when in ancient Rome). This system has frequently been featured as a main part of the show. The TARDIS, and by extension a number of its major systems, including the translator, are telepathically linked to its pilot, The Doctor. None of these systems appears able to function reliably when the Doctor is incapacitated.

Farscape

On the TV show Farscape John Crichton is injected with a conceivable bacteria, called translator microbes, which functions as standard (likely de facto) form a Universal Translator. The microbes colonize at brain stem and translate for the host anything spoken to him/her/it, and, then passing along the translated information to the host's brain. This does not enable the injected person to speak other languages, they continue to speak in their own language and are merely understood by others as long as they possess the microbes. The microbes sometimes fail to properly translate slang, translating it literal meaning. Also, the translator microbes are unable to translate the natural language of the alien Pilots because every word in their language can contain thousands of meanings, too much for the microbes to translate (Pilots must learn to speak in "simple sentences"). The implanted can learn to speak new languages if they want or to make communicating with non-injected individuals possible. The crew of Moya learned English from their human friend John Crichton, later visited Earth and were able to communicate with the non-implanted populace. Some species such as the Kalish cannot take translator microbes because their body rejects them so they must learn a new language the hard way.

Futurama

Almost everybody in the Futurama universe speaks English, with no explanation being given, though it is possibly because Earth seems to be a fairly dominant planet in galactic politics. A Universal Translator does exist, created by Professor Farnsworth, but while it can translate any language, it can only translate them into French (which, by the year 3000, is a dead language; in the French version of Futurama, the dead language is German).

Farnsworth: And this is my universal translator. Unfortunately so far it only translates into an incomprehensible dead language.

* Cubert: Hello.

* Universal Translator: Bonjour!

* Farnsworth: Crazy gibberish!

FreeSpace

In the FreeSpace series, there is a rough translator used to translate the Vasudan language to English (and possibly vice versa.)

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

Further information: Babel Fish

In the universe of "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy", universal translation is made possible by a small fish. The fish is inserted into the auditory canal where it feeds off the mental frequencies of those speaking to its host. In turn it excretes a translation into the brain of its host.

The book remarks that, by allowing everyone to understand each other, the babel fish has caused more wars than anything else in the universe.

The book also explains that the babel fish could not possibly have developed naturally, and therefore proves the existence of God as its creator. Since God needs faith to exist, and this proof dispels the need for faith, this therefore causes God to vanish "in a puff of logic".

The Last Starfighter

Alex Rogan was taken to the Starfighter Command on Rylos, where he was later given a chip that was attached to the collar part of his shirt, so Alex could hear English from the Rylos race and other alien races.

Star Control

In the Star Control computer game series, almost all races are implied to have universal translators; however, discrepancies between the ways aliens choose to translate themselves sometimes crop up and complicate communications. The VUX, for instance, are cited as having uniquely advanced skills in linguistics and are able to translate human language long before humans are capable of doing the same to the VUX. This created a problem during the first contact between Vux and humans, in a starship commanded by Captain Rand. According to Star Control: Great Battles of the Ur-Quan Conflict, Captain Rand is referred to as saying "That is one ugly sucker" when the image of a VUX first came onto his viewscreen. However, in Star Control II, Captain Rand is referred to as saying "That is the ugliest freak-face I've ever seen" to his first officer, along with joking that the VUX name stands for Very Ugly Xenoform. It is debatable which source is canon. Whichever the remark, it is implied that the VUX's advanced Universal Translator technologies conveyed the exact meaning of Captain Rand's words. The effete VUX used the insult as an excuse for hostility toward humans.

Also, a new race called the Orz was introduced in Star Control II. They presumably come from another dimension, and at first contact, the ship's computer says that there are many vocal anomalies in their language resulting from their referring to concepts or phenomena for which there are no equivalents in human language. The result is dialogue that is a patchwork of ordinary words and phrases marked with *asterisk pairs* indicating that they are very loose translations of unique Orz concepts into human language, a full translation of which would probably require paragraph-long definitions. (For instance, the Orz refer to the human dimension as *heavy space* and their own as *Pretty Space*, to various categories of races as *happy campers* or *silly cows*, and so on.)

In the other direction, the Supox are a race portrayed as attempting to mimic as many aspects of other races' language and culture as possible when speaking to them, to the point of referring to their own planet as “Earth,” also leading to confusion.

In Star Control III, the K’tang are portrayed as an intellectually inferior species using advanced technology they do not fully understand in order to intimidate people, perhaps explaining why their translators’ output is littered with misspellings and nonstandard usages of words, like threatening to “crushify” the player. Along the same lines, the Daktaklakpak dialogue is highly stilted and contains many numbers and mathematical expressions, implying that, as a mechanical race, their thought processes are inherently too different from humans’ to be directly translated into human language.

Stargate

In the television shows Stargate SG-1 and Stargate Atlantis, there are no personal translation devices used, and most alien and Human cultures on other planets speak English. The makers of the show have themselves admitted this on the main SG-1 site, stating that this is to save spending ten minutes an episode on characters learning a new language (early episodes of SG-1 revealed the difficulties of attempting to write such processes into the plot). In the season 8 finale of SG-1, “Moebius (Part II),” the characters go back in time to 3000 B.C. and one of them teaches English to the people there. Fans have speculated that the language could have been secretly adopted then and carried on from planet to planet, leading to today’s situation in which most planets speak English. This interpretation is severely strained, to say the least; it entirely lacks any sort of scientific credibility, especially considering the fact that almost every alien race encountered in every Stargate series speaks nearly perfect, modern English, when a language would almost certainly change beyond recognition in that length of time.

A notable exception to this rule are the Goa’uld, who occasionally speak their own language amongst themselves or when giving orders to their Jaffa. This is never subtitled, but occasionally a translation is given by a third character (usually Teal’c or Daniel Jackson), ostensibly for the benefit of the human characters nearby who do not speak Goa’uld. The Asgard are also shown having their own “language” (apparently related to the Norse languages), although it is in fact English played backwards. (see Hermiod).

Given that the Asgard and the Ancients were existent in the same 'Alliance of Four Great Races', it is possible that English was used as the universal language mentioned in "The Torment of Tantalus". Considering also that both races play or played a pivotal role in the interplanetary relations of several galaxies, as well as dealings with the Goa'uld, this could be the explanation of the existence of English as a semi-universal language. This would mean that, instead of other planets speaking Earth-developed English, Earth is in actuality speaking Alien-developed English, and as the Asgard and Goa'uld are cited as the source of a number of other Earth languages, would seem to be the case.

Star Trek

In Star Trek, the Universal Translator was used by Ensign Hoshi Sato, the communications officer on the Enterprise in Star Trek: Enterprise, to invent the linguacode matrix in her late 30s. It was supposedly first used in the late 22nd century on Earth for the instant translation of well-known Earth languages. Gradually, with the removal of language barriers, Earth’s disparate cultures came to terms of universal peace. Translations of previously unknown languages, such as those of aliens, required more difficulties to be overcome. Like most other common forms of Star Trek technology (warp drive, transporters, etc.), the Universal Translator was probably developed independently on several worlds as an inevitable requirement of space travel; certainly the Vulcans had no difficulty communicating with humans upon making “first contact” (although the Vulcans could have learned Standard English from monitoring Earth radio transmissions).

Improbably, the universal translator has been successfully used to interpret non-biological lifeform communication (in the Original Series episode “Metamorphosis”). In the Star Trek: The Next Generation (TNG) episode “The Ensigns of Command,” the translator proved ineffective with the language of the Sheliaks, so the Federation had to depend on the aliens’ interpretation of Earth languages. It is speculated that the Sheliak communicate amongst themselves in extremely complex legalese. The TNG episode “Darmok” also illustrates another instance where the universal translator proves ineffective and unintelligible, because the Tamarian language is too deeply rooted in local metaphor.

Unlike virtually every other form of Federation technology, Universal Translators almost never break down. Although they were clearly in widespread use during Captain Kirk’s time (inasmuch as the crew regularly communicated with species who could not conceivably have knowledge of Standard English), it is unclear where they were carried on personnel of that era; possibly they existed as implanted devices before that practice was deemed too potentially dangerous and discarded by the era of Next Generation.

The episode “Metamorphosis” was the only time in which the device was actually seen. During Kirk's era, they were also apparently less perfect in their translations into Klingon. In the sixth Star Trek film, the characters are seen relying on print books in order to communicate with a Klingon military ship, since Chekov said that the Klingons would recognize the use of a Translator. Actress Nichelle Nichols reportedly protested this scene, as she felt that Uhura, as communications officer, would be fluent in Klingon. The novelization of that movie provided a different reason for the use of books: sabotage by somebody working on the Starfleet side of the conspiracy uncovered by the crew in the story, but the novelization is not part of the Star Trek canon.

By the 24th century, Universal Translators are built into the communicator pins worn by Starfleet personnel, although, since crew members (such as Riker in the Next Generation episode “First Contact”) have spoken to newly encountered aliens even when deprived of their communicators, some other factor must also be at work.

In some episodes of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, we see a Cardassian universal translator at work. It takes some time to process an alien language, whose speakers are initially not understandable but as they continue speaking, the computer gradually learns their language and renders it into Standard English (also known as Federation Standard).

Ferengi customarily wear their Universal Translators as an implant in their ears. In The Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (DS9) episode “Little Green Men,” the humans without translators are able to understand the Ferengi once the Ferengi get their own translators working. Similarly, throughout all Trek series, a Universal Translator possessed by only one party is able to audibly broadcast the results within a limited range, enabling communication between two or more parties, all speaking different languages. The devices appear to be standard equipment on starships and space stations, where a communicator pin would therefore presumably not be strictly necessary.

Since the Universal Translator presumably does not physically affect the process by which the user's vocal cords (or alien equivalent) forms audible speech (i.e. the user is nonetheless speaking in his/her/its own language regardless of the listener's language), the listener apparently hears only the speaker's translated words and not the alien language that the speaker is actually, physically articulating; the unfamiliar oratory is therefore not only translated but somehow replaced. This implies the Universal Translator may work at least partially on a telepathic level. There is no explanation why we could hear not-translated words like klingon.

Star Wars

The Star Wars films feature a situation where there is a galaxywide lingua franca, Galactic Basic, which sounds remarkably like English (although the written form, Aurebesh, replaces each letter with a different shape); it is unsure if the language is supposed to sound exactly like English, or if it is supposed to be “translated” into English. Unlike, for instance, the Stargate universe, the different species are shown to have their own languages (for instance, Huttese), which are “translated” for the viewer by means of subtitles, or a third character acting as an interpreter. The idea of a common language being spread throughout the galaxy is consistent with the Star Wars universe’s concept of a galaxywide unified government (the Old Republic) having existed for millennia.

Unreal

A Universal Translator machine can be found in the game Unreal as a usable item. It is mostly used to read Nali and Skaarj inscriptions from books, screens etc.

Non-device translators

Most of the time, the universal translator is depicted as a machine that works with a communications monitor. An exception is the Babel fish from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, a small organism that fits in the user’s ear. (The Babel fish itself is a parody of the universal translator convention.)

Another exception is the “translator microbes” from the Farscape series, which were probably inspired by the Babel fish.

In K. A. Applegate’s famous science fiction series, Animorphs, all Andalite warriors have miniature translator chips in their brains, which enable them to readily understand any spoken alien language. This is mentioned in The Hork-Bajir Chronicles and The Andalite Chronicles. However, in the series most aliens possess “thought-speak,” a type of telepathic communication, which operates more on the essence of thoughts than the words themselves; thus, an alien can thought-speak in their own language, but everyone hears it as their own. When morphed into a non-thought-speaking creature, such as a human, aliens seem to gain the ability to speak English, possibly due to a translator. Some aliens also seem to speak English without a translator, such as the free Hork-Bajir (who could have picked it up when they were Controllers interacting with Human-Controllers) and the last Arn (who explains that he studied the language, learning it quickly while in orbit). There is also a lingua franca called galard, used in communication between aliens capable of speaking it.